Methylmercury Poisoning

When people worry about mercury in fish, it’s organic methylated mercury they’re worrying about.

METHYLMERCURY SOURCES

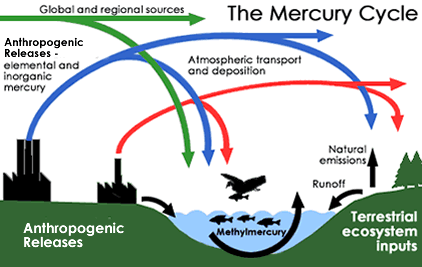

While there are a multitude of mercury chemicals, the ones that concern human life are methylated compounds of mercury. One major source of methylmercury is industry. The chlorine-chemical plants and pulp-paper mills have historically discharged fluids contaminated with methylmercury into rivers, lakes and oceans as part of their waste stream. This practice is now illegal in many places, like the United States and Sweden, but remains a common practice in other countries, especially at pulp paper mills.

Mother Nature is the other culprit for creating methylmercury. Inorganic mercury is introduced into the environment through volcanic eruptions, hot springs or the deposition of mercury minerals. Geological and meteoric processes like erosion and rainfall move these natural forms of mercury into lakes and rivers. Anaerobic bacteria in the bottom muds of freshwater rivers and lakes can methylate that mercury naturally, causing methylmercury to accumulate in bottoms muds in most underwater environments.

A third methylmercury pathway is through airborne pollution. Elemental mercury is introduced into rivers and lakes by rainfall or by the deposition of mercury-contaminated dusts. Once it arrives in bottom muds, the mercury gets methylated by the anaerobic bacteria and bioaccumulates as described above. Airborne mercury pollution sources include:

- mercury-enriched dusts from surface mining, especially from gold and coal mines

- mercury vapor from gold mine and mercury mine tailings and heap-leach piles

- coal-fired power plants

- non-point fossil-fuel pollution like automobile exhaust

This mercury pollution gets airborne as dusts and fumes. It is removed from the atmosphere by rain, snow or simply fallout. Some of it falls or is washed into rivers and streams where it becomes available to those bacteria in bottom muds who make methylmercury.

DON’T EAT THE FISH

Once methylmercury gets introduced or created in lakes and rivers, it gets taken up by phytoplankton and other algae forms. These get eaten by worms, aquatic insects and other invertebrates, which in turn get eaten by little fish. Little fish get eaten by bigger fish, and so on. In this way, methylmercury works its way up the food chain, getting a bit more concentrated every time it makes a jump upward.

Methylmercury is stable in most biological environments, including in fish and inside your stomach. Unfortunately, methylmercury is also fat (lipid) soluble. Fat soluble means that your body fat will suck it up and hold onto it, just like other unwelcome squatters in your body like pastries and ice cream; unlike the latter, however, methylmercury is highly toxic and can persist in your body for months to years before breaking down.

Poisoning by methylmercury is known as Minamata disease, named after a cluster of poisonings caused by eating contaminated fish in the Japanese town of Minamata. Methylmercury in fish was also the chemical involved in the Minamata disease clusters in Ontario, Sweden, and Niigata, Japan.

How Much Methylmercury in Fish is Too Much?

The danger of adverse effects from methylmercury in fish really depends on these things:

- your body weight

- how often you eat fish

- the type of fish you eat

- the contamination level of the fish you eat

These four things all play a role in determining whether you’ll get methylmercury poisoning from eating fish.

Methylmercury is a stealth poison: it takes eating a lot of fish over a long period of time before the adverse effects appear, typically months to years. The mercury content of the fish in the poisoning cluster in Minamata, Japan varied between 9 and 24 ppm or parts per million (measured as elemental mercury). The people in Minamata ate a lot of fish every day because it was a staple in their diet. It took time before the effects of chronic methylmercury poison showed up. Those symptoms were:

- loss of peripheral vision

- the feeling of “pins and needles” in hands, feet and lips

- clumsiness

- problems speaking, walking, and hearing

- muscle weakness

The Minamata poisoning cluster was an extreme case because no one knew back then what was causing the weird symptoms. It took time to identify methylmercury as the cause of Minamata disease. Once the culprit was known, the problem then became one of toxicology: how much methylmercury was too much?

After a lot of research, the U.S. FDA issued a general guideline in 1995 not to eat any fish with more than 1 ppm mercury. That’s a roughly a tenth of the lowest contamination measured at Minamata. It’s a level the FDA estimated to be generally safe based on the amount of fish that the average american eats. But where do such numbers really come from?

In 2000, the National Academy of Science reevaluated all known methylmercury research and confirmed that the existing “reference dose” for methylmercury at one microgram per kilogram was still the valid limit for human exposure. A reference dose is defined as the estimated daily exposure that is probably without risk of contracting any adverse affects when experienced over a lifetime.

Explaining how that reference dose was calculated is arcane. The dose-response behavior of methylmercury in humans is really complicated and figuring out a safe limit is not straightforward. It’s not ethical to design a study that deliberately poisons people with methylmercury in order to find out how much is too much. The reference dose is based on studies of fish eaters who were already exposed to methylmercury. The safe limit was determined by comparing adverse health effects with how much contaminated fish was eaten by people who were already showing symptoms of Minamata disease. The National Science Foundation study is referenced at the end of this article for those who want to slog through the methods and numbers.

What Methylmercury Dose Limits Mean

The way the dose thing works is this: you shouldn’t take in more than 1 microgram of methylmercury per kilogram of body weight on a daily basis. The catch is that the safe limit depends on your body weight.

Here’s an example. Let’s say a gal weighs 110 lbs. That’s approximately 50 kilograms. Using the reference dose limit, this lady should not take in more daily methyl mercury than:

- (50 kilograms) x (0.000001 grams) / kilogram = 0.000 050 grams = 50 micrograms

What does this mean in terms of eating fish?

Let’s say this gal loves eating tile fish, a yummy game fish found in the waters off the east coast of the USA. Tile fish can pack up to 1.45 ppm mercury (measured as elemental mercury).

Since it is a safe assumption that all mercury in fish is in the form of methylmercury, most tests for mercury content in fish are based on mercury alone. It’s quicker and easier to test for mercury than it is to test for methylmercury, so that’s actually a good thing; however, we need to convert between measured elemental mercury and the actual merthylmercury content in the fish in order to use the reference dose information.

The conversion is easy. The molecular weight of mercury is 200.6 grams/mole and the molecular weight of methyl mercury is 215.6 grams/mole. To convert ppm of mercury to ppm of methyl mercury, we calculate:

- 1.45 ppm mercury x (215.6/200.6) = 1.56 ppm methylmercury

This means that the 1.45 ppm of mercury in tile fish corresponds to a methylmercury content of 1.56 ppm, which is the same thing as a concentration of 1.56 milligrams per kilogram. A quarter pound serving of tile fish weighs 113 grams. The total amount of methyl mercury in that 4 ounce serving is:

- 0.113 kilograms x 1.56 milligrams / kilogram = 0.176 milligrams = 176 micrograms.

That’s more than three times the safe daily limit of 50 micrograms for a 110 pound person using the National Academy of Science reference dose. Time to skip the tile fish. If you ate tile fish every day for several months, you might start having some of the adverse health effects of chronic methymercury poisoning. This is an example for how to convert the toxicology information available on methyl mercury in fish into numbers that make sense in the real world. Of course, if you don’t eat a lot of fish, you could probably get away with having that tile fish. If you ate fish all the time, maybe you would want to reconsider.

Dose depends on weight. If our fish lover weighed 250 pounds instead of 110, then the safe reference dose would be 113 micrograms instead. Once again, 176 micrograms of methyl mercury in the tile fish is still greater than the safe daily limit.

It needs to be said that the reference dose is daily limit for a lifetime. That’s actually a really weird concept since infants, children and people with compromised health are more susceptible to methylmercury poisoning than healthy adults. It’s also a number based on statistics, large groups of people, and multiple scientific studies. It’s an averaged result. The problem here is that no one is average. Some people are more prone to poison effects than others. This is why toxicology is not for people who hate statistics or for folks who want hard and unmovable answers in life. The reference dose is the probable safe daily limit because there’s always someone out there for whom the reference dose is just plain wrong. That’s why government warnings and regulations are always more cautious than the results of toxicology studies. When it comes to public health, the government endeavors to err on the side of safety.

Who is in Really in Danger from Methylmercury?

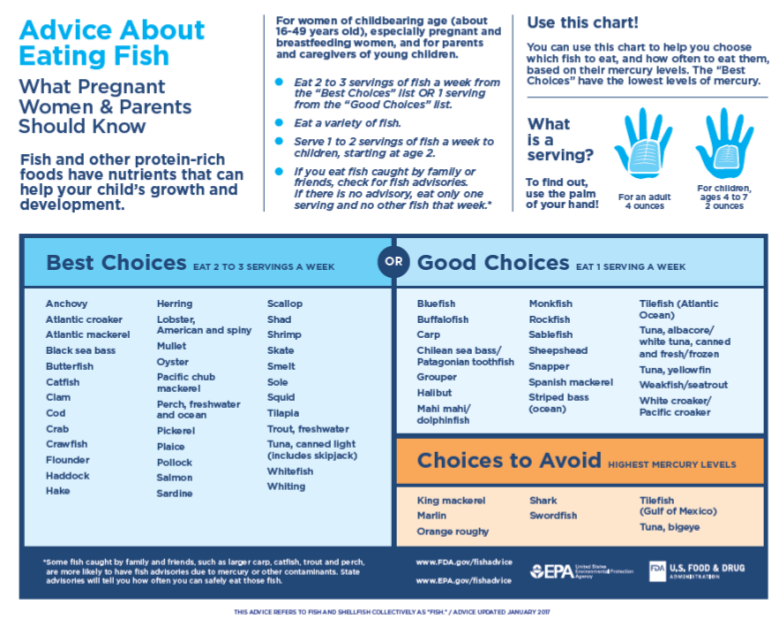

In a soundbite, pregnant women, unborn children, infants and small children are the people in the most danger from methylmercury. This isn’t to say that other people aren’t in danger if they eat a lot of mercury-tainted fish, but it’s the young of our species who have disproportionately reaped the worst harm from methylmercury poisoning in the form of mental retardation, birth defects and neurological disorders. Minamata disease is ugly and scary – but it can be avoided by avoiding fish species known to accumulate methylmercury. It’s that simple. There’s lots of good information out there on what fish to avoid, especially when pregnant. Several websites with this information are listed at the bottom of this page in the Sources section.

Methylmercury in Fish: Bad News and Good News

The bad news is that eating fish is how people get methylmercury poisoning. The neurological damage is essentially permanent for infants and children. Since mercury is difficult to remove from the body, the outcome of adults is not good either. Once you suffer adverse health effects from exposure to methyl mercury, the damage will be devastating and it will last for the rest of your life. If you’re a mother, pregnant or have kids in the house, you really want to be cautious about eating certain kinds of fish. That’s the bad news.

The good news is that most healthy adults can dodge the damage by limiting or avoiding fish known to pack high levels of mercury. If you just can’t live without your tuna sushi, then you can choose to indulge less often. Eat more wild salmon and trout and less halibut. Switch to chicken salad for sandwiches. There’s no need to panic over methylmercury in fish; a little caution will go a long way.

Skip the fear and instead, educate yourself about the hazard

It’s easy to make intelligent decisions about the fish you eat based on the published knowledge that’s easily available. There are lots of guidance out there on which fish to eat and which to avoid. The FDA chart shown above is a one good source and the fish webpage at the World Mercury Project is another. The mercury-in-fish page at Wikipedia has a handy chart of average contamination levels by species if you want to dig deeper into the numbers.

SOURCES AND GOOD WEBSITES TO VISIT

All these websites were accessed on July 21 and 22, 2017. A government agencies cited are part of the US federal government.

- Boston University webpage on Minamata Disease

http://www.bu.edu/sustainability/minamata-disease/

- Center for Disease Control – Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxfaqs/TF.asp?id=113&tid=24

https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/PHS/PHS.asp?id=112&tid=24

- Environmental Protection Agency

https://www.epa.gov/mercury/how-people-are-exposed-mercury#methylmercury

https://www.epa.gov/mercury/basic-information-about-mercury

https://www.epa.gov/choose-fish-and-shellfish-wisely

https://www.epa.gov/mercury/health-effects-exposures-mercury

- Food and Drug Administration

https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/02/briefing/3872_advisory%207.pdf

https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/FoodborneIllnessContaminants/Metals/UCM537120.pdf

- National Academy of Sciences Textbook on Methylmercury Toxicology

https://www.nap.edu/catalog/9899/toxicological-effects-of-methylmercury

- Oak Ridge National Lab Mercury Risk Assessment Study

https://rais.ornl.gov/tox/profiles/mercury_f_V1.html

- Pub Med abstract on methylmercury

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3514465/

- World Mercury Project webpage on fish

https://worldmercuryproject.org/mercury-facts/mercury-in-fish/

- The banner graphic is from the cover of a report on methylmercury contamination at the Grassy River First Nation Reservation in Ontario.

2 thoughts on “Methylmercury Poisoning”

I see many articles on Methylmercury and the health effects on a infants brain but what about Ethylmercury on the infants brain? Also what about the long term effect on the brain of both infants and adults?

Other than the consensus that ethylmercury does not bioaccumulate, and has an bio-halflife of 7 to 10 days in adults, I’m not as good with this compound as I am with methylmercury. My dissertation and two decades of professional environmental science work in California put me in the ranks of someone who can talk about methylmercury in the environment as a scientific authority. Ethylmercury is a different beast, however, despite that fact that the names sound familiar. They are produced in different ways and have different bio-organic pathways. Methylmercury is way way bad; ethylmercury doesn’t hold a candle to methylmercury. Ethylmercury is not nice stuff but it’s not anywhere near as lethal or damaging as methylmercury. But it would take a doctor doing biochem research on organo-mercury compounds or a mercury toxicologist to really speak authoritatively on its effects – and I’m not one of those.

When I was sampling streams destroyed by acid mine drainage downstream of abandoned mercury mines in California as part of my dissertation research, a researcher at a different institution on the other side of the country had ONE DROP of methylmercury penetrate the nitril glove on her hand while working in her lab and it killed her over nine months of progressively destroying her nervous system. It was a huge shock in the environmental and toxicology research communities when it happened. My faculty freaked and shelved my research until I could reassure them that my sampling program wouldn’t do the same to me. That’s what methylmercury does – it destroys people. Ethylmercury doesn’t work the same way because it doesn’t stay in the body. Both elemental Hg and ethylmercury leave the body on a timescale of days while methylmercury doesn’t leave and instead bioaccumulates and destroys the nervous system, resulting in Minamata disease degeneration and ultimately death. It’s a big difference.

The place I’d recommend you look at, if you have the chops to read up on chemistry and toxicology, is pubmed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/

Pubmed really is the place I go to when I need to research a biochem subject, especially since I am really far better at physical chemistry and geochemistry than biochemistry. I can usually get a good feel for what the bio, biochem and medical types think about a particular subject by reviewing abstracts and papers on pubmed. Meta-studies and survey papers are usually the best for figuring out a consensus in a field, or alternatively, if there isn’t a consensus and the “experts” are still arguing something out.

The other places to look for decent info are the toxfaqs hosted by the CDC and also chem data sheets at NIOSH.

Sorry I don’t know more off the top of my head than this. Good luck on finding good info. CDC and NIOSH are reliable so my advice is to check them out.