a Brief History of Spark Plug Insulation

Today we look at something I know you’ve all been wondering about for years. Well wonder no longer for enlightenment on this electrifying subject is now here!

WHY CARE ABOUT SPARK PLUG INSULATORS?

History-of-technology stuff is really cool. I hope you get as much a charge out of this as I did.

In 1902, Gottlob Honold and Robert Bosch built the first true magneto ignition system with the first-ever high-voltage spark plugs. Though there have been many improvements since then, the basic principles of gas engine ignition designed by Honold and Bosch are still the same.

Spark Plug Design

Ever since 1902, the overall design of high-voltage spark plugs has three parts:

- The central electrode. This is a conductive material, usually metal, that carries an electric charge to a combustion chamber in a gasoline engine.

- The insulator. It wraps around the central electrode and insulates it.

- The plug body or jacket. This is the conductive casing around the insulator and central electrode. A second electrode is attached to the plug body. There is always an air gap between the central and second electrode.

When a charge is delivered to the central electrode of a spark plug, that charge will jump the air gap between the electrodes as a spark. If the timing is right, then the spark will ignite the fuel-air mixture in the engine cylinder. Thus the spark plug is the thing that ignites the combustion in a gasoline combustion engine. Needless to say, it’s important for the spark plug to work well.

Part of working well includes effective insulation. It’s bad if electricity can jump from the central electrode to the conductive plug body at a location other than the electrodes. Therefore, the material used as the insulator is crucial for the spark plug to work well.

Porcelain Spark Plug Insulators

The first spark plug insulators used something known as refractory porcelain. This is a ceramic made out of a high-quality clay that can survive really-high temperatures. The clay-mineral kaolinite is the primary ingredient. If you have seen white-ceramic laboratory wares used to heat and melt things, that’s one example of refractory porcelain. In the United States, the Coors company has been one of the major producers of refractory porcelain.

Refractory porcelain was the logical first choice for spark plug insulators but it had some problems which were quickly discovered. Notably, porcelain was brittle. When it heated up, it also did not expand as much as the metal in the electrode or plug body. As a result, the earliest porcelain insulators didn’t last very long before they broke.

Mica Spark Plug Insulators

On of the first materials used to add to or replace porcelain was mica.

- Mica is a silicate mineral notable for the combined properties of heat resistance, flexibility and strength.

- A variety of this mineral called book mica had been used for furnace windows for centuries.

- Book mica was easy to get and wasn’t expensive.

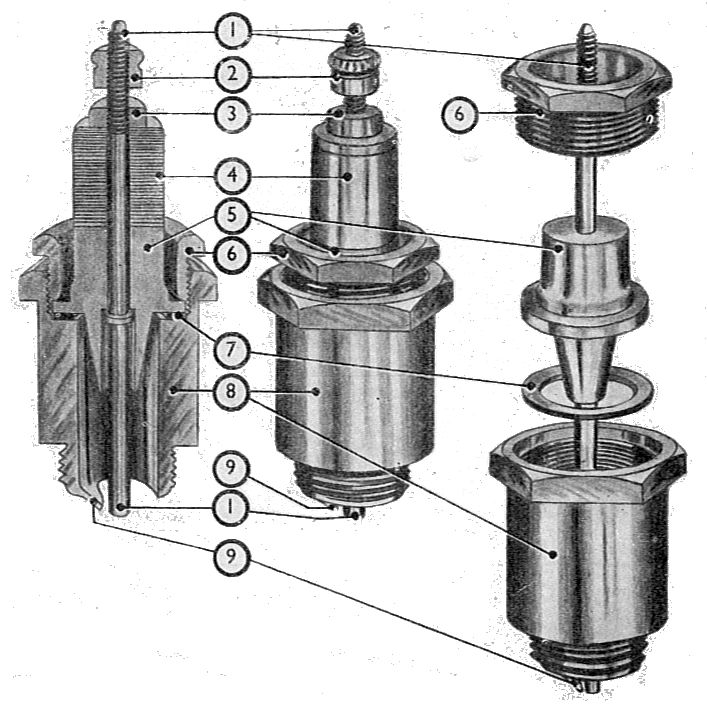

Mica was used in spark plugs right up to World War II. An example of mica in a spark plug is shown in the figure below:

1) Central electrode,

2) Terminal nut,

3) Insulator locknut, or electrode nut,

4) Insulator mica rings,

5) Insulator body (porcelain),

6) Assembly nut,

7) Copper-asbestos washer,

8) Plug body,

9) Side electrode.

Steatite Spark Plug Insulators

One of the problems with mica as an insulator was the build up of carbon deposits, which fouled up the conduction of electricity through the central electrode. In addition, mica was not as good as porcelain in insulating against stray electric currents.

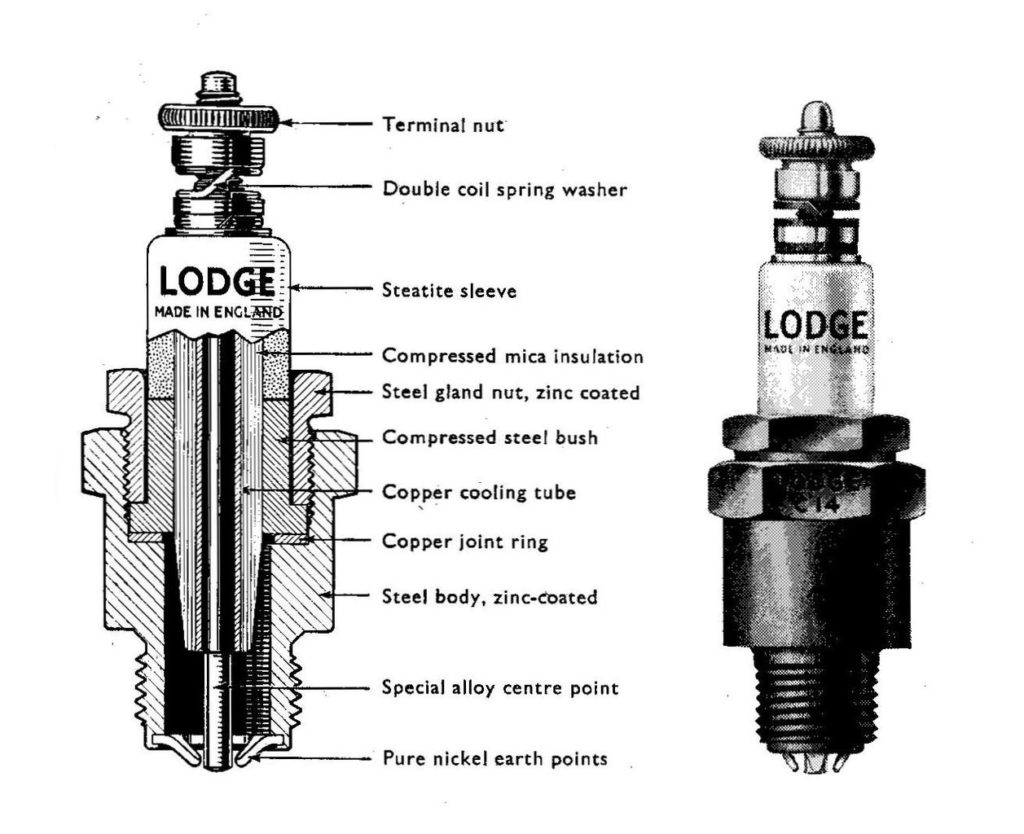

One of the other mineral used to compensate for the weaknesses of mica and porcelain was steatite. Most people know steatite by its common name of soapstone. It’s a rock that’s mostly talc. Because it’s not as strong and flexible as mica, it was often used with mica, like the spark plug design shown below:

Andalusite-Sillimanite Insulators

Only the Champion brand of spark plugs used sillimanite as an insulator, from 1921 until 1945.

Most of the sillimanite in spark plugs started life as the mineral andalusite, initially mined from the Champion Mine in the Inyo-White Mountains, not too far from Death Valley in California.

Andalusite has a chemical formula of Al2SiO5. When you heat this mineral up, it converts to the mineral form of sillimanite, which also has a chemical formula of Al2SiO5. The difference between the two minerals is that sillimanite is a superior material for both thermal and electric insulation. It beat porcelain, mica, steatite and their combinations hands-down.

The andalusite deposit at the Champion Mine was a one-of-a-kind mineral body. No one in the world had anything like it. Champion essentially had a monopoly on this material.

Sillimanite-insulated spark plugs were by far the best available. Every race car and almost every air plane engine used Champion plugs throughout the world because of their reliability and long-life.

One other andalusite-and-sillimanite mine eventually opened up outside of Lovelock, Nevada for providing spark plug insulators. It too was owned and operated by Champion.

THE END OF MINERAL-BASED SPARK PLUG INSULATORS

Other spark plug companies did not care for the dominance of Champion and its monopoly on andalusite and sillimanite. In the 1930s, both Siemens in Germany and AC Spark Plugs in the United States pioneered the use of sintered alumina as an insulator material. Sintered alumina has almost the same thermal expansion as the metal parts in a plug along with three times the strength and insulating ability compared to sillimanite. As soon as War World II was over, sintered alumina replaced all the mineral-based spark plug insulators because it really was a superior material for the job.

The Champion Mine in Inyo County, California, remains one of the most famous mining locations among mineral enthusiasts to this day.

♠

All of the images used in this article are in the public domain.

4 thoughts on “a Brief History of Spark Plug Insulation”

And… what is the rest of the story? What are we using today? Did Champion stop making there spark plug totally? And what is the porcelain looking sheath? Or does the mineral used just look like that also?

Does older machines react well to new fangled spark plugs? Was the output spark the same?

Champion still makes plugs. They use sintered alumina like everyone else.

The porcelain-looking sheath on the photo at the top of the blog post and on the spark plugs in your car are all sintered alumina. The stuff looks like porcelain.

Old cars do quite will with sintered alumina spark plugs. The big difference is that a sintered alumina plug is going to last a lot longer than one using a mineral-derived insulator. The engine will be run better too since there will be fewer timing faults due to spark leakage. Unlike software, alumina-insulated spark plugs are fully backwards compatible.

I am an A&P with a IA, and Got my license in 1969. I am working on a Tiger Moth WW1 aircraft. The barrel of the spark plug I was told, was coated with Mica. This clear coating is now coming off. What can I replace this coating with? I need your help!!!!

Larry

I’m afraid I won’t be much help here. I’m far better with mineralogy than I am with mechanical engineering. If the clear stuff coming off is mica, this might be tricky. Mica is a mineral. The form used industrially is still sold in either thick blocks (“book mica”) or as thin sheets for furnace and lamp windows. Getting mica is not the problem. The problem I foresee is that I have no idea how to get the thin sheet mica used for furnace windows to wrap around a barrel without breaking and then to stay in place.

Mica is not a coating and I don’t know of any way to make mica into a coating. Given the heat involved, there aren’t any liquid adhesives or aglutenants that I know of that won’t burn off, so mixing up mica powder (yes, there is such a thing) with a heat-resistent glue probably won’t work.

This assumes that what’s coming is indeed mica. It might not be. I suspect that you probably are trying to rehabilitate a spark plug made by Lodge Plugs Ltd. in England. You might try to find out more about how the Lodge made its spark plugs that were used in the Tiger Moth engines.

You might try consulting with some aircraft museums. The folks who maintain and restore WWII aircraft from England are also in the same boat of trying replace or rehabilitate Lodge brand sparkplugs. You might find some help there.

Sorry I don’t have better information for you.